Maori Mythology: A Window into Cultural Values and Beliefs

Maori mythology, a rich tapestry of stories passed down through generations, offers a captivating glimpse into the cultural values and beliefs of the Maori people of New Zealand. These myths, often woven into intricate narratives featuring powerful gods, mythical creatures, and ancestral heroes, provide profound insights into the Maori worldview, their understanding of the natural world, and their interconnectedness with the past, present, and future.

The Realm of Māori Mythology: An Introduction

Maori mythology is a vibrant and complex system of beliefs and stories that encapsulates the Maori way of life. These narratives, passed down orally for centuries, serve as a powerful tool for transmitting knowledge, values, and cultural identity. They are not merely fantastical tales but deeply ingrained in the Maori understanding of creation, ancestry, and the interconnectedness of all things. The stories are often rooted in the natural world, drawing inspiration from mountains, rivers, forests, and the creatures that inhabit them. This close connection to nature underscores the importance of respect for the environment and the belief that humans are part of a larger, interconnected ecosystem.

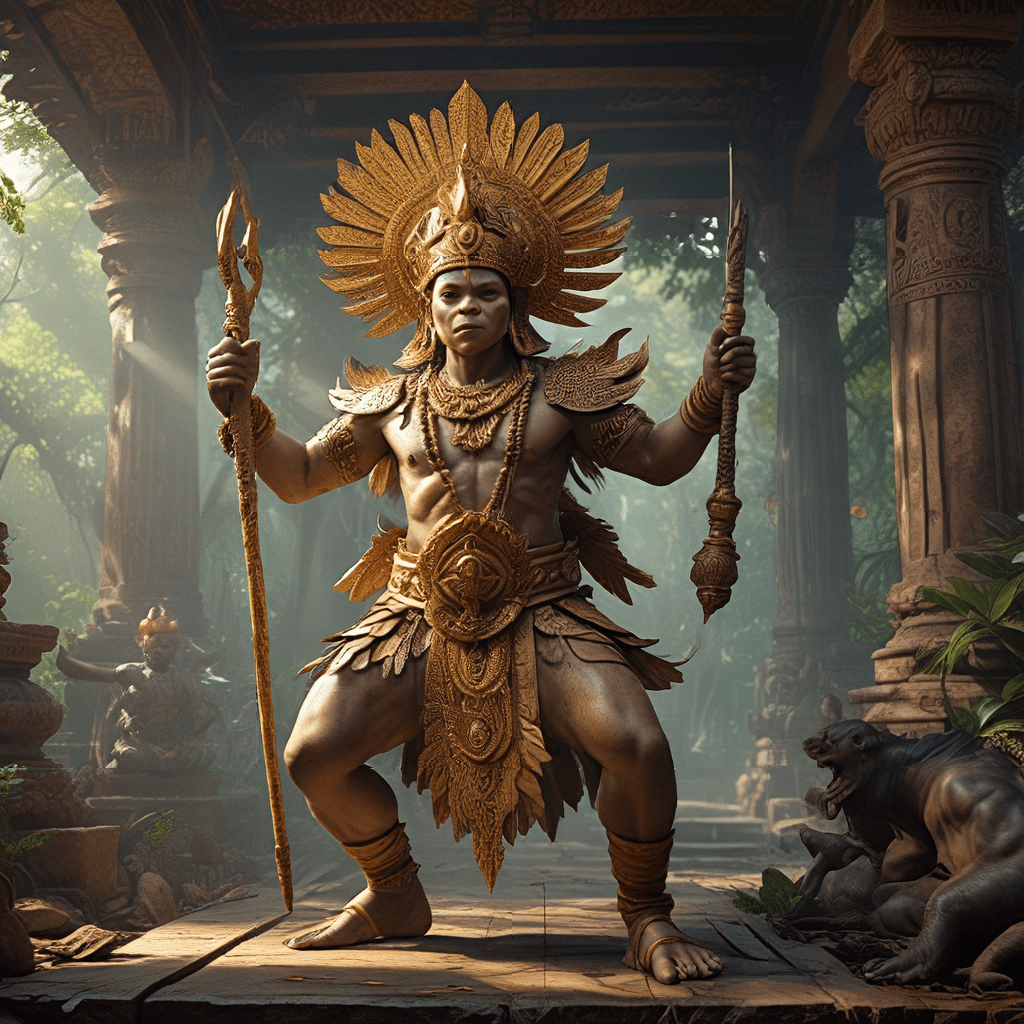

Key Figures in Māori Mythology: Gods, Goddesses, and Beings

Maori mythology is populated by a diverse cast of gods, goddesses, and mythical beings, each with their unique roles and significance. Some of the most prominent figures include:

- Tane Mahuta: The god of forests and birds, credited with shaping the world and bringing forth life.

- Rongo: The god of agriculture, responsible for the bounty of the land.

- Tangaroa: The god of the sea, representing the vast and powerful ocean.

- Hina: The goddess of the moon, associated with femininity, fertility, and the tides.

- Maui: A trickster demigod known for his cunning and bravery, credited with feats such as fishing up the North Island of New Zealand and stealing fire from the gods.

- Rūaumoko: The god of earthquakes and volcanoes, embodying the powerful and unpredictable forces of nature.

- Tiki: An ancestral figure representing the first human, often depicted in carved statues and believed to possess spiritual power.

These deities and beings play intricate roles in shaping the narratives and conveying cultural values.

The Creation Myth: Te Kore, Te Pō, and the Birth of the World

The Maori creation myth narrates the emergence of the world from a state of nothingness, Te Kore, into existence. This process is described in two phases: Te Kore (the void) and Te Pō (the night). From Te Kore, the primordial state of nothingness, emerges Te Pō, a state of darkness and potential. Within Te Pō, the gods, led by Tane Mahuta, begin the process of creation. Tane Mahuta, the god of forests, separates heaven and earth, bringing forth light and life. The creation myth establishes the fundamental belief in the interconnectedness of all things, highlighting the importance of balance and harmony within the natural world.

The Importance of Ancestry and Lineage: Whakapapa and the Connection to the Past

Whakapapa, the Maori concept of genealogy, plays a pivotal role in understanding their cultural values and beliefs. It refers to the intricate system of tracing lineage back to ancestral gods and beings, connecting individuals to the past and the land. Every person, place, and thing has a whakapapa, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all living things. Whakapapa is more than a genealogical chart; it's a powerful tool for understanding cultural heritage, social responsibilities, and connections to the land. It is a vital aspect of Maori identity and provides a framework for understanding the present through the lens of the past.

The Concept of Tapu (Sacredness) and Noa (Common)

Tapu and noa are two powerful concepts in Maori culture that influence their worldview and behavior. Tapu, meaning sacred or forbidden, refers to things or places that are considered sacred and require respect, reverence, and avoidance. Noa, on the other hand, signifies common or ordinary, referring to things or places that are not restricted by tapu. The concepts of tapu and noa are interwoven into various aspects of Maori life, including rituals, food practices, and social interactions. Tapu is often associated with gods, ancestors, and special places, while noa represents everyday life. The balance between tapu and noa is crucial for maintaining harmony and order in Maori society.

The Role of Spirits and the Supernatural: Atua, Māui, and the Realm of the Dead

Maori mythology is rich with spirits, supernatural beings, and the belief in a spiritual realm. These elements are woven into their stories, traditions, and daily lives. "Atua," meaning gods or spirits, are an integral part of Maori cosmology. They are not seen as distant, aloof beings but as active participants in the world, influencing natural phenomena, human affairs, and even the fate of individuals.

One of the most famous and revered figures is Māui, a trickster demigod known for his cunning and bravery. Māui is credited with several legendary feats, including fishing up the North Island of New Zealand, capturing the sun, and stealing fire from the gods. His stories teach valuable lessons about resourcefulness, problem-solving, and the importance of courage in the face of adversity.

The concept of "Te Po," the realm of the dead, is also a significant aspect of Maori beliefs. The journey of the soul after death is described in detail, highlighting the importance of honoring the deceased and maintaining a connection with the ancestors. The afterlife is not necessarily seen as a place of punishment or reward but rather a continuation of existence, with the ancestors playing an active role in shaping the lives of the living. This belief emphasizes the importance of respecting the past and honoring the legacy of the ancestors.

The Significance of the Natural World: Mountains, Rivers, Forests, and Animals

The Maori worldview is deeply intertwined with the natural world. Mountains, rivers, forests, and the creatures that inhabit them are not simply resources but are seen as living entities with their own spirits and stories. Each feature of the landscape is considered sacred and holds a special significance within the Maori framework.

Many mountains, rivers, and forests are named after mythical figures, deities, or significant events in Maori history. These names act as reminders of the deep connection between the Maori people and the land. The natural world was a source of sustenance, inspiration, and spiritual guidance. Animals, such as the kiwi, the moa, and the whale, often feature prominently in Maori mythology, representing specific qualities or serving as metaphors for human behavior.

The interconnectedness of humans and the natural world is reflected in their concept of "whanaungatanga," which emphasizes the importance of family, community, and responsibility for the well-being of the environment. This deep respect for the natural world is evident in their traditional practices of resource management and conservation.

The Importance of Community and Cooperation: The Concept of Whanaungatanga

"Whanaungatanga" is a key concept in Maori culture that emphasizes the importance of family, community, and shared responsibility. It is a powerful framework that guides social interactions, decision-making, and the overall well-being of the community.

Whanaungatanga is not just about blood ties but also about the interconnectedness of individuals within a broader community. It is based on the principle of "mana," a concept that encompasses respect, authority, and responsibility. Individuals are expected to act in a way that upholds the mana of their family, lineage, and community.

This concept fosters a sense of unity and cooperation, ensuring that individual actions are aligned with the collective good. Whanaungatanga is reflected in various aspects of Maori life, from traditional ceremonies and gatherings to the way they manage resources and make decisions. It serves as a guiding principle for maintaining social harmony, fostering a sense of belonging, and supporting each other through times of adversity.

The Impact of Māori Mythology on Art, Music, and Dance

Maori mythology has a profound impact on their art, music, and dance, serving as a powerful source of inspiration and expression. Stories, deities, and mythical figures are often depicted in elaborate carvings, taonga (treasures), and other forms of traditional art.

For example, the iconic "tiki" carvings, often found on meeting houses and other significant structures, represent ancestral figures, embodying strength, protection, and connection to the past. These carvings are not merely decorative but are imbued with spiritual significance, serving as reminders of the ancestors and their enduring influence.

Maori music, with its powerful vocals, intricate rhythms, and traditional instruments, is deeply rooted in their mythology. Songs and chants often recount historical events, tell stories of gods and heroes, or express emotions and beliefs. Similarly, Maori dance forms, like the "haka," are infused with symbolism and meaning, often depicting stories from mythology, showcasing their cultural identity, and igniting a sense of pride and unity.

Modern Interpretations and Adaptations of Māori Mythology

Maori mythology continues to be a vital part of modern Maori culture, evolving and adapting to contemporary contexts. Contemporary artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers are drawing inspiration from traditional stories and reinterpreting them in new ways.

These adaptations reflect the ongoing process of cultural revitalization and the desire to connect with the ancestral wisdom of the past while addressing the challenges of the present. Maori mythology is not static but is a dynamic system of beliefs and stories that continues to influence and shape the identity and cultural expression of the Maori people, both in New Zealand and beyond.

FAQ

Q: What are some important figures in Maori mythology?

A: Tane Mahuta, Rongo, Tangaroa, Hina, Maui, Rūaumoko, and Tiki are some of the most prominent figures.

Q: What is the significance of whakapapa?

A: Whakapapa is the intricate system of tracing lineage back to ancestral gods and beings, connecting individuals to the past and the land.

Q: What is the role of the natural world in Maori mythology?

**A: ** Mountains, rivers, forests, and animals are seen as living entities with their own spirits and stories.

Q: What is whanaungatanga?

A: Whanaungatanga emphasizes the importance of family, community, and shared responsibility, fostering a sense of unity and cooperation.

Q: How has Maori mythology influenced modern culture?

A: Maori mythology continues to inspire art, music, dance, literature, and film, reflecting the ongoing process of cultural revitalization.